Is everyone indebted to China?

“Japan, Japan, Japan,” JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon once said in an interview. When he was coming up through Harvard Business School in the early 1980s, it seemed to be what everyone was talking about. Now, it seems, everyone is talking about China. Why?

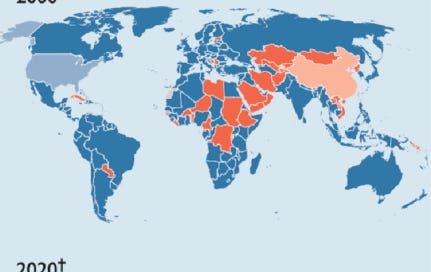

The last few decades have witnessed an extraordinary improvement for China’s economic affairs, from manufacturing, GDP growth, trade, global finance, technology advancement, and more. This image from The Economist summarizes this growth better than others:

At first, these changes impressed economists for obvious reasons. An explosion in real GDP growth translates to real improvements in human well-being. Over the last few decades, for example, the number of people living in extreme poverty has been cut in half. This is in large part because a huge segment of the once-poor Chinese population has been able to drastically improve its economic station.

Now, however, economists are concerned about such a power dynamic. If autocratic China continues its meteoric rise — from a share of less than 25 percent of global trade to a share just shy of 75 percent in the last 20 years — where will that leave the rest of the world? Not only does a powerful China impact other global superpowers like the U.S. and EU, it also affects the economic station of poorer nations.

What happened

“In a lot of the world, the clock has hit midnight,” a recent Fortune headline said, quoting Harvard economist Ken Rogoff. The clock has hit midnight because a lot of the world owes China a lot of money, and that bill is coming due.

“A dozen poor countries are facing economic instability and even collapse under the weight of hundreds of billions of dollars in foreign loans,” the article continues, “much of them from the world’s biggest and most unforgiving government lender, China.”

As part of China’s so-called Belt and Road Initiative, in which President Xi Jinping wants to build a sprawling trade and supply chain network throughout much of the world, many countries took on loans from China to improve their own infrastructure. Fortune describes Zambia, who has borrowed billions from Chinese banks over the past 20 years, as one such situation in which the lender has proven to be unforgiving:

The loans boosted Zambia’s economy but also raised foreign interest payments so high there was little left for the government, forcing it to cut spending on healthcare, social services and subsidies to farmers for seed and fertilizer.

… [A] group of non-Chinese lenders refused desperate pleas from Zambia to suspend interest payments, even for a few months. That refusal added to the drain on Zambia’s foreign cash reserves, the stash of mostly U.S. dollars that it used to pay interest on loans and to buy major commodities like oil. By November 2020, with little reserves left, Zambia stopped paying the interest and defaulted, locking it out of future borrowing and setting off a vicious cycle of spending cuts and deepening poverty.

Inflation in Zambia has since soared 50%, unemployment has hit a 17-year high and the nation’s currency, the kwacha, has lost 30% of its value in just seven months. A United Nations estimate of Zambians not getting enough food has nearly tripled so far this year, to 3.5 million.

A similar story has played out for other nations like Pakistan, Ethiopia, Sri Lanka, and the Republic of Congo. Leaders in the U.S. have previously described this situation as “economic coercion,” where heads of state can use the mechanics of finance to influence the leaders of other countries to behave a certain way.

Why it matters

What’s now troubling is that, for many, the global economic outlook is souring. We’ll continue to see these two consequences.

First, poorer nations will have difficulty paying back the loans they took on because their exports or productivity will decline or have done so already. Just as Zimbabwe faces a deteriorating economic situation due to these loans, other countries will as well: The war in Ukraine, inflation, worsening unemployment, and more are all made worse when a country is drowning in debt. As The Washington Post describes, “China is now the world’s largest government creditor to developing nations, accounting for nearly 50 percent of these loans, up from 18 percent in 2010, according to the World Bank. These Chinese loans were often at high interest rates. It would have been a stretch for poor nations to repay them even in good times, and now it’s impossible after a global pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine have decimated low-income economies where people are struggling to afford food.”

Second, China’s own economic situation is worsening, and that will increase their desperation for getting their money back. Thanks to strict measures to contain COVID, collapsing real estate valuations, slowing growth, economic sanctions, and an aging workforce, many economists think the Chinese economy is worse than the data portrays. Not only has the Chinese government lent money to foreign nations to build up their infrastructure but it’s also lent money to its own cities to do the same. The Economist recently recounted several such cities, whose pressure from their debts is “immense” and “at a breaking point.” Goldman Sachs estimates that local Chinese officials are burdened by $23 trillion in government-owned debt.

There’s also a larger context. According to investor Ray Dalio, when there’s a rising power challenging a declining power — especially when accompanied by social, financial, and technological disorder — there is usually major conflict. In this case, Dalio argues the U.S. empire is in decline, while the Chinese empire is on the rise. Another prominent investor and economist Nouriel Roubini recently described the politics affecting this conflict and why why “America and China are on a collision course.”

China is the second largest economy and is quickly becoming a global leader in important industries and materials such as manufacturing, as well as electric vehicles and other advanced technology, of which it produces 45 percent of the world’s solar silicon. For these and other reasons, The Economist writes, “Joe Biden is determined that China should not displace America.”

Tensions are high among many politicians, economists, and journalists over what seems like an inflating balloon that’s destined to pop. When, why, and what its total effects will be are unclear, but it is certainly another kind of inflation we definitely don’t want to experience much longer.1

This post was originally published on Common Good.