What’s the value of a marketing agency in the age of AI?

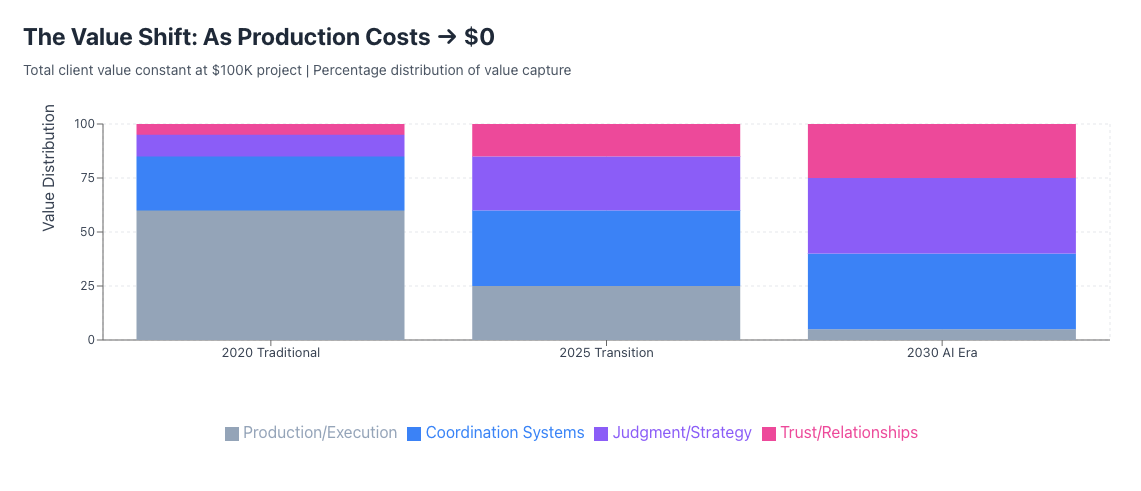

New AI tools push marketing production costs toward $0. As a result, the value for marketing teams—or really most knowledge workers—shifts from production toward coordination, judgment or strategy, and trust or relationships. Even further still, I’d argue it’s always been and will ever be about telling stories. Here’s a visualization I was working on with Claude.

Think of the printing press. Books used to be so costly that a church or school had one manuscript that needed to be read aloud, where congregants or students would copy the text only if they had the resources for parchment and ink. Others had to memorize it.

After presses published books by the thousands, driving printing costs to near zero, ideas proliferated, fueling the Reformation and Enlightenment movements. It also standardized practices, like punctuation and double-entry bookkeeping, the latter fueling an economic boom by improving trade.

Yet the roles within that idea proliferation changed dramatically. Scribes became less useful, like typists in the twentieth century. What grew in value was the role of the editor or publisher—their taste decided what was influential and what wasn’t. It turned out that deciding what wasn’t said was more valuable than the ability to say anything.

The same dynamic is playing out now. In a world where anyone can do and say anything, the value lies in knowing what not to do or say, or knowing where to place your limited resources. Additionally, when the quantity of content explodes, value lies in coordinating and editing, in building processes that standardize and streamline that power, thus improving quality, into effective media.

But even more than that, the real value lies in our ability to tell stories.

Jarrod, AD, and I were talking about this the other day when Jarrod told the story of Homo naledi, a prehistoric species related to the Homo genus living some 300,000 years ago in northern South Africa. There’s a debate among paleontologists that Homo naledi buried their dead at the bottom of a long shaft in a dark and difficult cave. Why? There had to be a story that compelled them to do so, as we have stories compelling us to bury our dead today.

If we’ve been telling stories for 300,000 years, the argument goes, there’s no reason why we’re not going to be storytellers even with AI tools. A December article in The Wall Street Journal described how the biggest companies today are desperately seeking so-called storytellers, and paying handsome sums for them.

The value for a marketing agency, then, lies in our ability to create strategies and processes that coordinate, care for, and clarify your story to the right people in the right way.

That’s what we aim to do.

As always, we’re grateful to serve.