Should Christians use LBOs?

Perhaps LBOs are moral decisions. In other words, the assumptions embedded within financial transactions are made with an implicit or explicit moral framework or worldview.

A leveraged buyout, or LBO, is a model for buying businesses. When one business wants to buy another, the buyer can use any mix of equity, debt, or assets to do so. But how much equity? How much debt? That's where an LBO model comes in.

The point of any investment is to return more money than you invest. That's ROI. A similar metric is the internal rate of return, or IRR, which is the holy grail of corporate investments, including acquiring companies.

The less equity and more debt you bring to the table, the higher your IRR, which in the financial world is a good thing. You used someone else's money to acquire an asset, pay off the loan by fixing up the business or selling its assets, and you're left with the rest.

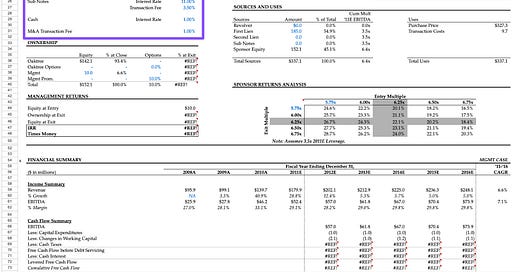

To estimate how much money you'll make, you can use a financial model like the LBO model below. Financial analysts input assumptions into the blue numbers to calculate IRR. They assign values to the loan amounts, interest rates, tax rates, fees, and cash, make other adjustments in the model for growth and valuation multiples, and let the spreadsheet handle the rest.

Traditionally, LBOs require lots of debt, sometimes 70% to 90% of the transaction, to provide the funds for an acquisition. This is the common approach for the often-vilified "corporate raiders" who take over companies, break up their assets, and lay off tons of people. The sum of the company's parts can actually be worth less than the individual parts, so new operators come in to extract value from the entire operation this way.

But perhaps these decisions are moral decisions. In other words, the assumptions embedded within financial transactions are made with an implicit or explicit moral framework or worldview surrounding them.

The number you enter for "minimum cash balance" reflects your risk appetite, your hope for the future, the amount to which you're willing to be enslaved to other investors or lenders. Your "exit multiple" reflects your understanding—or lack thereof—of current market expectations between buyers and sellers.

These decisions have real implications for how you behave as an investor or operator. And they get right to the heart of modern critiques of capitalism, particularly those of the far left who believe that corporations are greedy, billionaires are evil, and so on.

I recently heard a podcast with Permanent Equity founder Brent Beshore in which he argued that the amount of debt a company takes on for a typical LBO requires the buyer to make certain decisions regarding the time horizon and therefore how they'll treat the people working for the business, including employees, suppliers, and so on.

Similarly, Yale theologian Kathryn Tanner once argued that modern finance-driven capitalism collapses the past and the present for many who live in those societies. For example, a decision made when you were young, like taking out a student loan, has many effects years or even decades later, forcing you to make certain decisions that you otherwise wouldn't make simply because of your need to service the debt. Your past collapses into your present.

Of course, any decision works this way. The difference is that many things can be forgotten or redeemed. Your debt, however, cannot be forgotten or redeemed, and there are more opportunities to be indebted today than there ever have been. This is especially true in a consumerist society where more is always better. Mary Hirschfeld in her book called Aquinas and the Market argues that this is the primary cause of so many problems: The need for just 10% more.

In a similar vein, a client and I recently discussed on his podcast the trend toward commercial real estate collateralized loan obligations, or CRE CLOs. A few years ago, these were popular financial products because interest rates were rock bottom. Investors could secure low-interest loans, buy real estate, and then sell the loans, keeping the buildings with very little equity invested, driving up the IRR on the acquisition.

Unfortunately, many of those loan terms included floating interest rates, which means the rates increase with the market. As the Fed increased rates to slow down inflation, CLO rates skyrocketed, leaving buyers holding the bag. The loan terms were often at 3-year maturities, which means that that money is due now. Investors need to refinance, extend the maturity, or put up cash to pay off the loan. Over $40 billion in office loans and nearly $14 billion in apartment loans are currently in distress, with over $150 billion more in "potential" distress, according to a recent article in the Wall Street Journal.

What will this distress create not only in the broader real estate market but in the individual lives of the investors and operators, as well as those who live in the apartments?

It seems obvious to me that God's fingers work closely with interest rates, as well as the little blue numbers we enter into financial models.

I'm working on narrowing a research question for a PhD application, and questions like these on the ethics of finance—how money can be used to bring about good moral order—have me hooked. I think the question I'm asking is more than "how much debt is too much?" It's about worldview or moral ecology, but I'm still tinkering. What comes to mind are Old Testament laws like gleaning, usury, or Jubilee that baked into Israel's moral economy a concern for the poor. In other words, Israel's financial models required a line item for "the poor," an ancient blue number in their spreadsheet, that altered the value of their transactions, and allowed space for a healthier society overall.

If you have any resources on such a question, especially academic influences, I'd love to know.

Thanks for reading.