In the economy, it’s really what you know.

When you’ve arrived at the grocery store in the last few months, did the prices surprise you? Did you decide to buy the usual or not to buy that steak or your favorite cereal? Many people are feeling the pinch at the counter and, as The New York Times reported in May, “changing their habits.”

Why do we change our habits based on a number? There is the obvious answer, but it’s about more than our wallets.

Knowledge is an economy’s scarcest resource: We can’t possibly know every complexity that goes into every transaction we make at all times.

Two main challenges confront us here: Knowledge is disparate. And knowledge is implicit. First, our economic activity requires acting on this widely dispersed information. Knowing what to prepare for dinner, for instance, requires knowing how much groceries will cost, which requires farmers to know how much seeds and fertilizer cost and how much their harvest will yield, which requires fertilizer manufacturers to know how much their inputs and distribution will cost, and so on. Second, much of human knowledge just can’t be transmitted because it’s learned through experience. Try teaching someone to ride a bicycle by writing a letter.

Coordinating this information — whether as buyers, sellers, or government agencies — to reach, and work for, all of society requires just one number: a price. We discussed this briefly in a column last year: In a famous essay, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” Nobel-laureate economist Friedrich Hayek argued that it’s impossible for a person or group to know enough information to effectively make those allocation decisions. Soviet economists, for example, had to keep track of more than 24 million prices. Hayek suggests that a better strategy would be to harness widely dispersed knowledge.

To help the average person understand the principles of economics without all the math and fancy charts, building on the work of Friedrich Hayek, Thomas Sowell wrote a book called Basic Economics. In the chapter “The Role of Prices,” Sowell describes how every society — whether defined as capitalist, socialist, or something else — must carefully allocate resources, whether that’s knowledge, food, or fertilizer. This, he explains, is the point of economics.

How prices work

A price is the best way humans have to harness this overwhelming amount of information. “How an incredibly complex, high-tech economy,” Sowell writes, “can operate without central direction is baffling to many.” Prices, however, transmit all the myriad market-based information from every person in that market to the next person instantaneously. They tell us what to make and how to make it, as well as what to buy and how to buy it. They incentivize us to use our resources wisely.

This is never more important than in a shortage — of any kind. When an economic shock occurs, like in a natural disaster or a pandemic, some products become very scarce, and their prices reflect this reality by moving sharply. It comes down to supply and demand. Think of face masks in March 2020 or gas prices this past summer or flashlights during a power outage. If the prices of flashlights skyrocket, Sowell explained, “a family that might otherwise buy multiple flashlights for its members is more likely to make do with just one of the unusually expensive flashlights — which means that there will be more left for others.”

Prices tell us what to do.

Labor in short supply

Among many other shortages in our economy, there is the supply of labor. And labor comes at a price, too. The Wall Street Journal reported that “the labor force is about 600,000 smaller than in early 2020,” and “several million smaller if you adjust for the increase in population.”

And an industry desperately in need of labor is ministry. According to a Barna study cited earlier this year in the Journal, “Among pastors under age 45, nearly half were considering quitting.” One pastor interviewed in the article accepted the challenges of serving as a pastor, including “the 70-hour workweeks, the low pay, the calls from parishioners at all hours,” to experience “the joy of seeing people come to the faith.” But eventually he could no longer financially provide for his family on the salary. He left his church after eight years to work at a bank, where “he works regular hours now … and earns almost 39 percent more.”

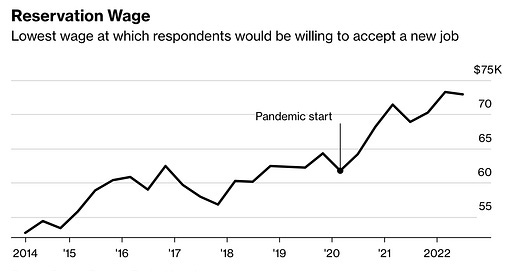

The current labor shortage may be partly due to the fact that the suppliers of labor (workers) and the demanders of labor (employers) can’t agree on the right price. A Bloomberg article published this week noted the rise of the “reservation wage,” or the lowest wage workers would be willing to accept at a new job. The figure? Nearly $73,000.

As costs have risen throughout the world for basic goods and services, workers have demanded a higher wage to make up for their lost purchasing power. This inevitably pushes prices up even further, since employers need to raise prices to justify the higher price of labor. You can see how this creates a vicious cycle known as the “wage-price spiral.”

Reading the room

As they do, prices are telling many people what to do, and the price of labor incentivizes people just like any other. Ministers, for example, may feel that ministries are communicating to them, through their low salaries, that there isn’t enough demand for their services. Banks, on the other hand, may be communicating to them through the offer of a higher salary that the demand for banking services is high — and there a minister could set a higher price for their labor.

You may be thinking this, too — that the prices you’re paid aren’t worth your labor and the complications that come with it. Perhaps you’re feeling the tug of another job or opportunity. Perhaps you’re worn out as a minister or leader of a non-profit organization — all the politics and long hours have become too much. Like the price of goods, the price of labor points to more factors than one.

What are the prices you see today telling you? How do you respond to the information? Think of your salary, your costs, and your people’s salaries and costs too — what knowledge are you sharing by the prices you set?

Prices, Sowell wrote, “can summarize the end results of a complex reality in a simple number.” These questions may be hard to answer, but that’s to be expected. Knowledge is, after all, our scarcest resource.

This post was originally published in Common Good.