How to face the economy fearlessly

To know where the economy is headed, it’s helpful to look where it’s been. Investor and author Ray Dalio might know this better than anyone. He founded what is now the world’s largest hedge fund — Bridgewater Associates.

In the latest chapter of his life, he’s dedicated his time to teaching others the principles that have made him successful, including principles for investing and economics. Over the last few years, two of his videos have stood out as being supremely helpful for me in understanding the latter. I know they can help you, too.

How the Economic Machine Works is a 30-minute primer on the basics of what we see playing out in the news today (and every day, for that matter). The second, Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order, describes in 45 minutes how nations rise and fall, and where we are currently in that cycle.

These are the best videos to understand how the economy works, and I encourage you to set aside an hour and a half to watch them in full. But if you don’t have the time, promise me you’ll save it for later, and keep reading here to get a grip on the current state of affairs.

HOW THE ECONOMIC MACHINE WORKS

The economy works like a machine, based on a few basic transactions repeated over and over again, which are all based on human psychology. These mechanics generate productivity growth as well as short- and long-term debt cycles, and by understanding these three concepts, you can begin to understand where we are in the economic cycle and what is likely to happen.

The economy is simply the sum of its transactions. A buyer buys what a seller is selling. One person’s expense is another’s income.

You can buy with money or credit, and these two equal the economy’s total spending. Total spending divided by the total quantity sold equals the prices buyers are willing to pay. That’s the entire economy. Of course, you can divide the economic pie further to see individual markets. A market is all the transactions for the same thing, like wheat or cars.

And let’s not skip over the concept of credit. What most people consider money is actually credit. Credit is great: It allows us to pull forward purchases for our future selves into the present, which allows us to grow our productivity when we buy productive assets like cars, factories, or businesses.

Credit is what fuels the economy. The more credit in the market, the more incomes and asset prices rise, and people feel richer. Remember that one person’s expenses are another’s income: More income equals more spending, which equals more income for someone else and so on. A boom cycle begins.

However, when we pull those future purchases into the present, we borrow against our future selves. This is the shadow side of credit, and it’s bad only when it fuels over-consumption on nonproductive assets like big-screen TVs and fancy cars. The lender now has an asset (credit) while the borrower has a liability (debt). This is why we have cycles. Credit sets into motion a mechanical series of events that will take place in the future.

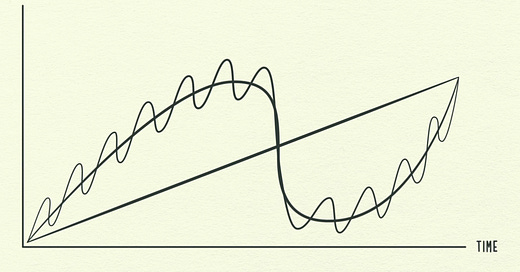

In this graphic, Dalio depicts a simplified version of the short-term debt cycle (the squiggly line), the long-term debt cycle (the sloped curve), and productivity growth (the straight line).

The short-term debt cycle typically lasts around 5 to 8 years, while the long-term debt cycle lasts around 75–100 years. Credit is important for the short-term cycle, while productivity growth is central to the long-term cycle. It’s productivity that’s the real engine of the economy; without it, we’re all just spending someone else’s money, and our future selves are worse off.

So, to slow down exuberant spending booms, the central bank plays an important role in the flow of credit. The head of the central bank is the chair of the Federal Reserve. Today, that’s Jerome Powell.

Powell, along with his board of governors, are now trying to create what Dalio calls a “beautiful deleveraging.” Deleveraging is what happens when the short-term debt cycle — fueled by exuberance and overconsumption — deflates without causing a depression. Put simply, deleveraging is preferable to a depression as a way to wrangle the economy.

Powell and his board can control interest rates and money printing. Printing money speeds up the economy by encouraging spending, which is what we saw happen in 2020 — this is an inflationary activity. Raising interest rates slows down the economy by reducing spending, which is what we’re seeing happen now — this is a deflationary activity — and it’s the first step in a beautiful deleveraging.

In a deleveraging, the central bank needs to, over the course of several years, see that interest rates rise to reduce spending, debt is defaulted on or restructured, wealth is redistributed, and social and political tensions remain low. But it’s a process that needs to be carefully balanced. If these things happen too quickly, the central bank can induce a depression. This means that asset values, incomes, and employment quickly fall. In that case, economic participants — that’s you — realize that what they thought was money is actually credit, and their debts become unbearable.

This can create a lot of problems, externally and internally. The poor blame the rich, the left blames the right, and vice versa. Political and social tensions mount. Dalio provides three rules of thumb for individuals and policymakers to combat these problems:

Don’t have debt rise faster than income, since you’ll increase the debt burden.

Don’t have income rise faster than productivity, since you’ll be uncompetitive.

Do all that you can to raise productivity, since in the long run that’s all that matters.

If this advice isn’t followed, economies can lose their place in the world order.

THE CHANGING WORLD ORDER

It seems that the times ahead will be radically different from what we’ve experienced in our lifetimes, but similar to what’s happened many times before. It’s always been this way, and it will always be this way. As a global macro investor, Dalio says the most surprising events never happened in his lifetime, but they have happened many times before. So for perspective, he studied the last 500 years of history to understand what’s happening today.

In 1971, gold was the medium of exchange between countries. Money was like checks in a checkbook. However, it quickly became apparent to the economic powers in the United States that the country would soon run out of this “real” money, or gold.

So, on August 15, 1971, President Nixon declared on national television that the U.S. was breaking its promise to let people exchange their dollars for gold. It wasn’t stated that way, of course. Nixon said it more diplomatically; people didn’t think that we were actually running out of money.

Dalio, then a trader on the stock floor, expected the stock market to behave poorly, so he got onto the floor early to prepare. But the market went up 25 percent over the next 18 months. He was wrong in his prediction because, at the time, he didn’t understand that the exact same thing happened in 1933, to the same effect.

Breaking the link to gold allowed the U.S. to spend more than it earned since it printed money. Since more money entered the economy without productivity increase, this caused asset prices to rise. Less powerful dollars means you need more of them to buy things, which is another way of describing inflation. Over the next decade, inflation became a serious problem, much like it seems to be today.

This has happened many times before.

As an aside, Dalio instructs, when central banks print a lot of money, individuals should buy stocks, gold, and commodities because their value will rise and the value of money will fall.

So what does this have to do with a changing world order? And what is a world order? It’s simply a governing system for people dealing with each other — internal orders are created with documents and institutions (such as constitutions), and external orders are created after major wars, such as treaties and trade agreements.

Dalio and his team, reading the history this time, realized that three things always happen, like a machine going through the motions:

When countries eventually can’t pay down their debt, they print money.

This leads to increasing internal conflict. Think of how the economic events of 2008 and 2020, along with widening inequality, created political polarization between the left (who want to redistribute wealth) and the right (who want to defend those holding wealth).

This internal conflict eventually leads to increasing external conflict, between a rising power and an incumbent power, like China and the U.S., respectively.

Think of the American revolution in 1776, the French revolution in the late 1700s, the Russian revolution in 1917, or the Chinese revolution in 1949. This sequence has happened over and over again, and the last time was between 1930 and 1945.

In 1944, the allied powers created a new monetary system during what’s known as the Bretton Woods Agreement. This established the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, which is the common medium of exchange around the world. If a country's currency is named the reserve currency, it's poised to become the richest and most powerful empire in the world.

The same thing happened with the British empire and the pound. It also happened with the Spanish, German, French, Indian, Japanese, and Ottoman empires and their conflicts.

To clarify and compare these great empires, Dalio and his team created an index to measure their relative power over time, which you can see below:

How does Dalio measure an empire’s power? He compiled data based on “eight strengths,” each of which lead to the next in a mechanical series, including:

Education

Innovation and technology

Competitiveness

Output

Trade

Military

Financial center

Reserve status

This is how the eight strengths grew relative to the U.S. since the beginning of the 18th century:

When you further simplify these strengths, you can more clearly see the cause-effect relationships:

It’s important to note that these strengths decline in a similar order. The rise and decline of these strengths create what Dalio calls “The Big Cycle.”

When a new empire enters the scene, there’s typically peace, prosperity, and productivity, since this period usually follows a major war. As stability increases, individuals and institutions use credit, or debt, to fuel production. Over time this can create an exuberant bubble, as illustrated above, and the economy over-stretches its productive capacity.

As this creates an economic downturn, the central bank is forced to print money. These events trigger those internal conflicts, which can lead to external conflicts, and the debt and political power gets restructured to form a new world order. This historically takes about 250 years, with 10- to 20-year overlaps in which incumbent powers vainly fight to the death against rising powers. History bodes ill for the U.S. But there are things we can do to thwart the march of time.

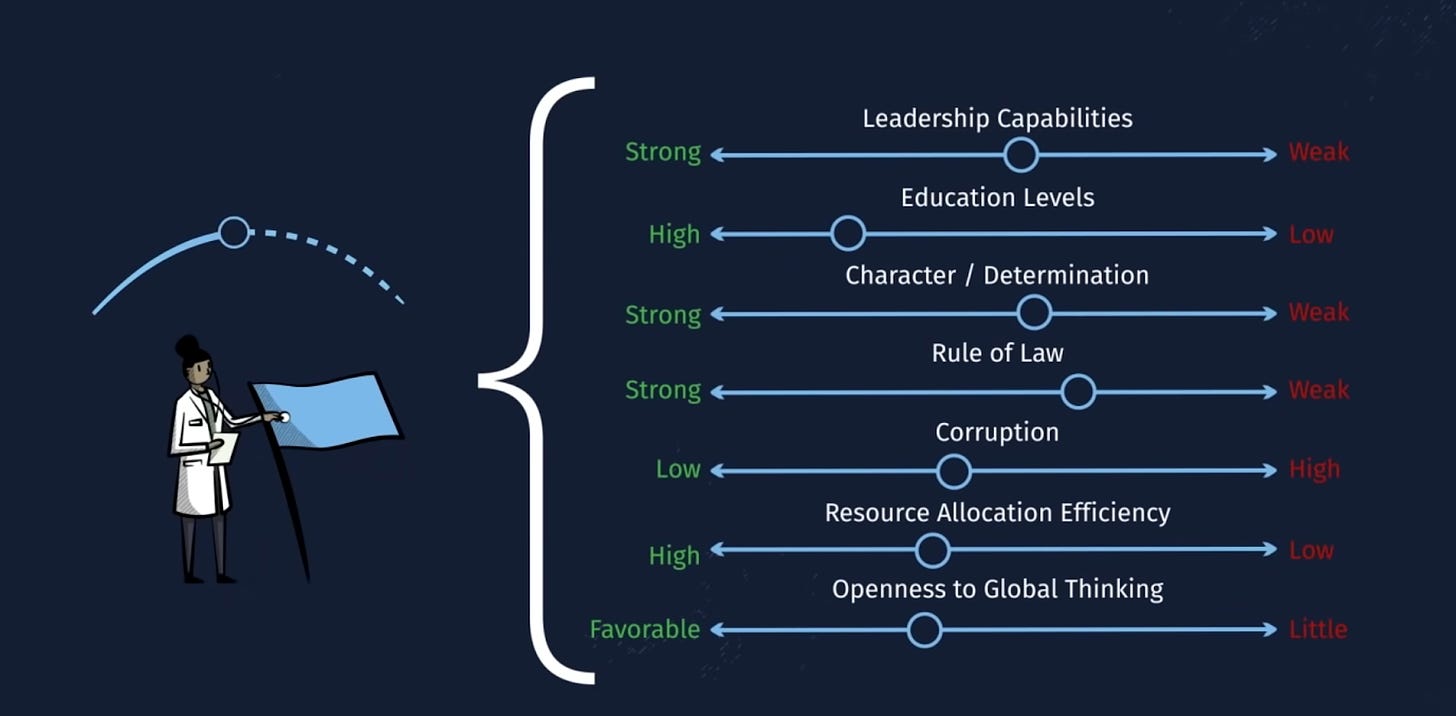

Empire life cycles look like human life cycles in their predictability. But longevity is a poor measure to estimate someone’s life cycle. It’s better to look at health indicators. The same is true with empires. Measuring indicators like leadership, education, laws, and others can help you anticipate what stage a country is in to see what’s likely to come next. This allows individuals and policymakers to intervene before things get too bad.

You can think for yourself about our country’s leadership capabilities, level of corruption, and resource allocation efficiency, among others, to analyze whether we’re headed in a good direction. Dalio’s advice is extremely useful in understanding how so much of economic life really does look like a machine built on cause-effect relationships.

And armed with this knowledge, you can begin to anticipate the future, and maybe even change it.

This post was originally published in Common Good.