Food, energy, cars, and the state of our economy

Last month, we talked about how the Fed raised interest rates. Now, the question is this: When do they stop?

Economists believe, according to Reuters, that the Fed will raise interest rates by half a percentage point in both May and June. Half of a point may not sound like much, but in the complex machinery of the modern economy, that’s a big number. Reuters polled economists to figure what may happen next, and many economists believe the probability of a recession is at 40 percent. Read last month’s Quick Notes if you need a refresher on how that works. But if you don’t have time for that — essentially, the Fed is trying to slow down inflation, which hit 8.5 percent in March, a four-decade high.

It’s important to remember this: A recession only means a slow down in GDP growth for two consecutive quarters. And remember what makes up that inflation number: the Consumer Price Index (CPI). We’ll cover that today.

ENERGY. FOOD. CARS.

The CPI is one among many indexes for measuring the price of a basket of goods, which helps determine how fast average prices are increasing. Many of the goods in that basket have had price increases lately, but three have had a larger impact on the CPI than others: energy, food, and cars.

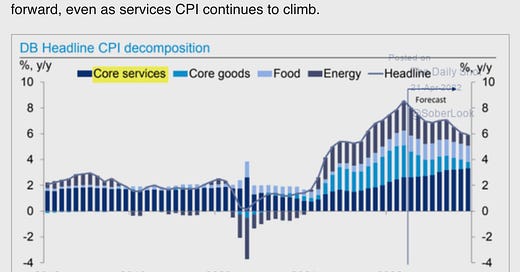

Take a look at the following chart provided by The Daily Shot via Deutsche Bank Research.

You can see that energy was a major factor in the beginning of the pandemic. And it still remains so today — but for the opposite reason. For a time, barrels of oil were sold for negative prices, which means someone was willing to pay you to store oil for them. This was because of supply chain issues at refineries and ports. Now, oil has drastically increased in price due to demand, largely thanks to the war in Ukraine and winter heating costs in Europe.

The second component, food, has been increasingly affected as the war in Ukraine wages. As I’ve noted before, Ukraine and Russia produce nearly a quarter of the world’s wheat, and Russia produces about 12 percent of the world’s oil. The problem now, however, is that the price of fertilizer has exploded. Creating fertilizer is an energy-intensive process, as Nobel laureate economist Paul Krugman pointed out this week. This could become an even more pressing issue in the future, since both energy prices and food prices continue to rise. Without fertilizer, the world could be short on wheat. And Ukraine, Russia, and China aren’t exporting much wheat at the moment. In the simplest terms, Krugman commented, “This is bad.”

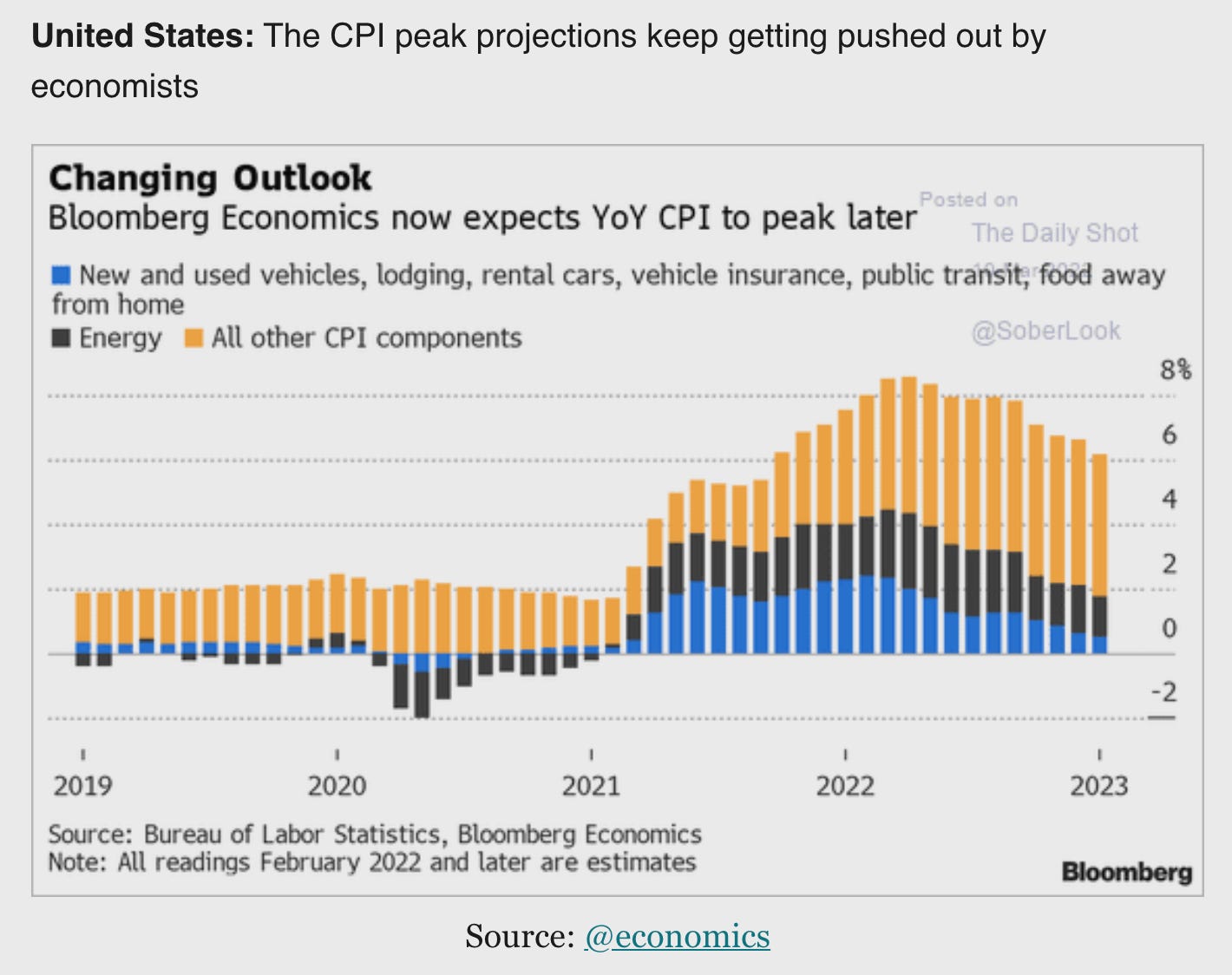

Third, cars have also been a major driver of this inflation. This second chart from Bloomberg via The Daily Shot shows how the prices of vehicles have contributed to the issues we’re seeing.

If you’ve tried to buy a car in the last year, you know the headache it’s become. Consumers are “revolting,” according to The Wall Street Journal, noting that dealers have increased prices considerably over MSRP. Plus, this all comes at a transition toward electric vehicles, in which most major auto companies are investing billions. “Auto executives and analysts expect the dearth of new cars and lofty prices to stick around at least into 2023,” the article reported. It’s a major disruption to a core part of the U.S. economy, and it’s likely to continue.

The state of these goods suggests inflation will be here for a while, and the Fed will have a very difficult time settling these through interest rates. In fact, they’ve never successfully reduced inflation by four percentage points, without raising unemployment.

Economist Timothy Lee, at Full Stack Economics, argues that because of four things — oil, rents, wheat, and supply chain disruptions — inflation won’t go away this year. And the last point is crucial. Ports in China are in even worse shape than they were in 2020.

SO WHEN WILL RATES STOP RISING?

We know that the Fed raises rates to slow down a hot economy. They aim to get back to a neutral state. “Key to that strategy,” Nick Timiraos records in The Wall Street Journal, “will be estimates of the neutral interest rate, a monetary nirvana that balances supply and demand when unemployment is low, the economy is growing steadily, and inflation is stable around the Fed’s two-percent objective.”

But that isn’t a simple objective, one chief economist noted: “The Fed only knows where neutral is in retrospect.”

A former Fed economist laid out two scenarios: First, the Fed raises rates until it reaches 4.25 percent next year, which brings down inflation to 2.5 percent in 2025. Or, people think inflation will continue to increase, in which case it will continue to increase, and the Fed can’t keep inflation below three percent for the rest of the decade. Maybe this last case is the one that will pan out. With that possibility, Timothy Lee believes that “policymakers still aren’t taking inflation seriously enough.”

WHO CARES?

You may be thinking, Okay, but I’m not an economist. I understand that. But here’s why this is important to you: Like the car buyers in this climate, people experiencing these high prices may continue revolting. The economy has such a transformative effect on people’s everyday lives. As the economy becomes unstable, so does society.

If you’re even slightly interested in how the dynamics might play out over the next decade or more, take 45 minutes to watch this video from Ray Dalio. Dalio founded the world’s largest hedge fund and, over the last few years, has devoted his energy to teaching the principles that made him successful. He’s written several books about that and the economy, including Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order, and in this video, he describes the effects of prices on people experiencing that change.

We’ll tackle the changing world order in more detail next time.

This post was originally published in Common Good.